History

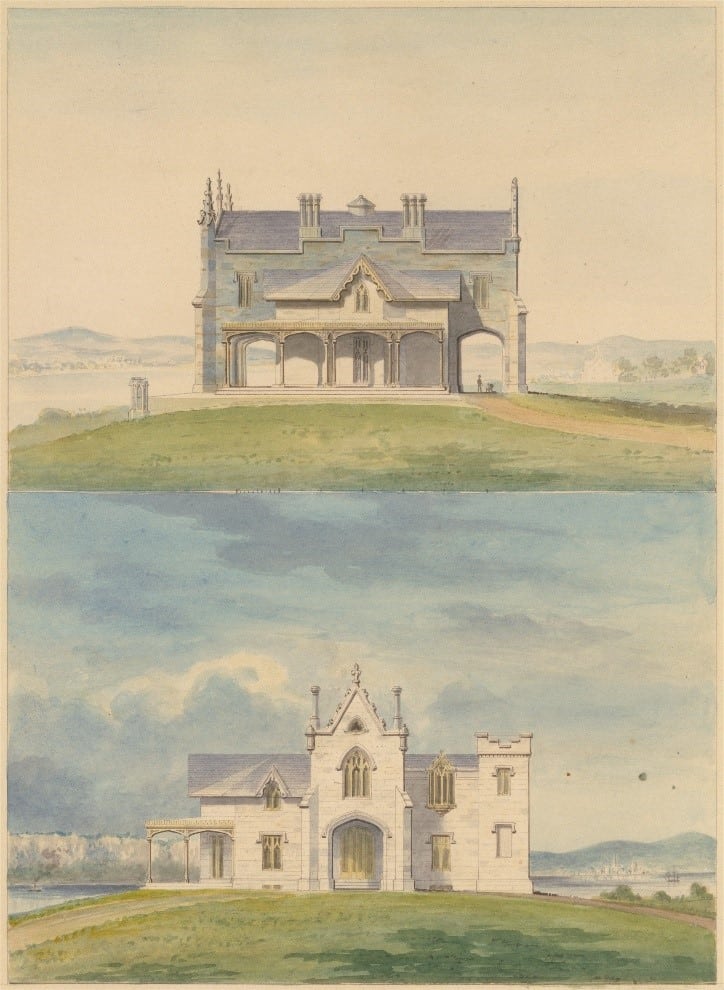

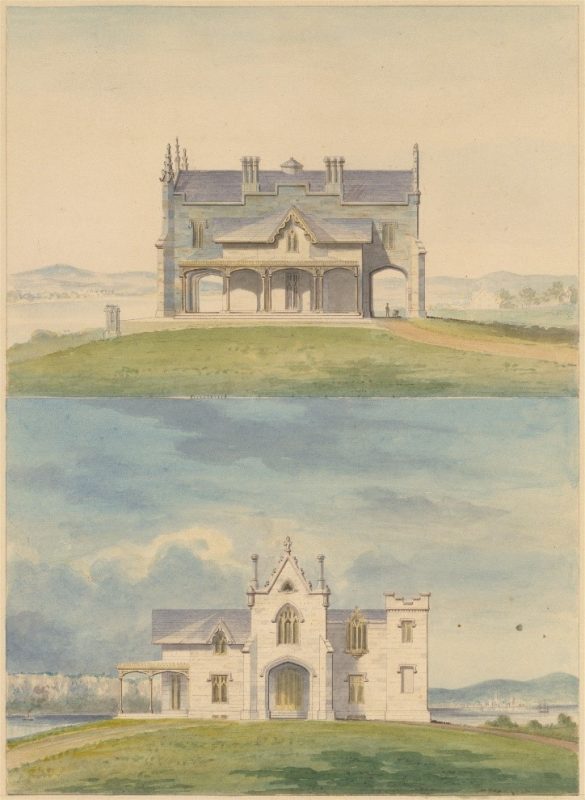

Overlooking the Hudson River in Tarrytown, New York, is Lyndhurst, one of America’s finest Gothic Revival mansions. Designed in 1838 by Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892), the mansion’s architectural brilliance is complemented by its comprehensive collection of original decorative arts and the estate’s park-like landscape.

The land on which Lyndhurst was built was originally hunting grounds of the indigenous Lenape/Munsee tribe that were the first inhabitants of the Hudson Valley. Sadly, their presence was all but gone by the turn of the 19th century in Westchester County. Originally woodland, it was cleared to become farmland in the 18th century by the early Europeans.

The estate was shaped for more than a century by three families and their staff: The Pauldings, The Merritts, and the Goulds. Their influence is evident in the expansion of the main house from a country villa “in the pointed style” to a Gothic mansion, the park-like design of the grounds, as well as in the rich furnishings and decorations inside.

The 19th century was a period of political and technological change in America. Romanticism dominated the arts, and the movement emphasized the appreciation of nature, imagination, and emotion as the Hudson River Valley became the center for painting and architecture. Wealthy patrons commissioned the construction of mansions in a variety of styles along the bluffs of the river from New York City to Albany.

|  |

William S. Paulding, Jr. (1770-1854)

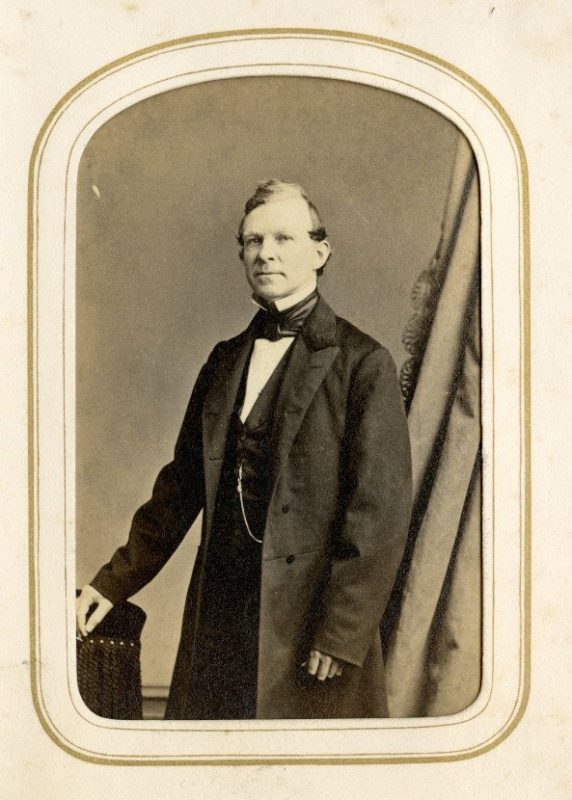

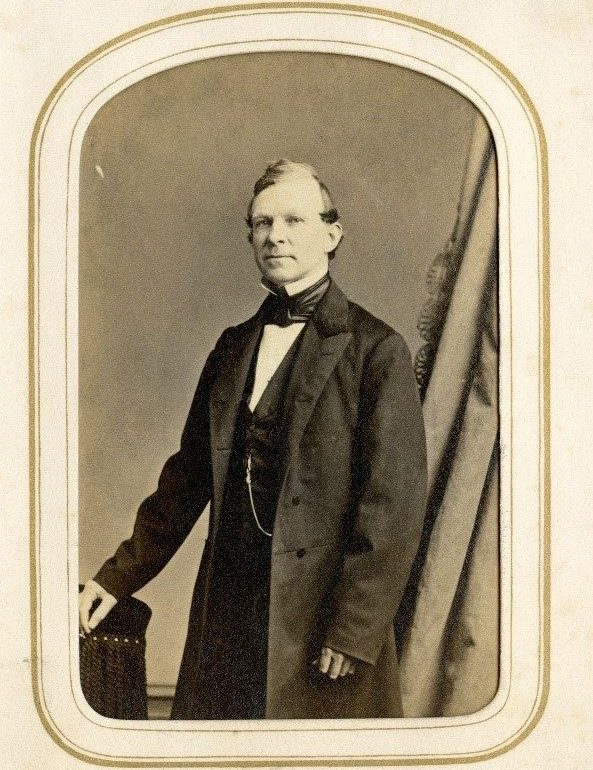

Lyndhurst was first conceived in the minds of architect Alexander Jackson Davis, William S. Paulding, Jr., and his son Philip R. Paulding. The elder Paulding commissioned the country summer villa in 1838. Paulding was a Tarrytown native in retirement after a career as a gentleman, military officer, and politician; he was a brigadier general during the war of 1812, a state representative, and a Mayor of New York City in the 1820s. Paulding was likely first introduced to the budding architect, Davis through Paulding’s family connections with Washington Irving, and other artists of the time.

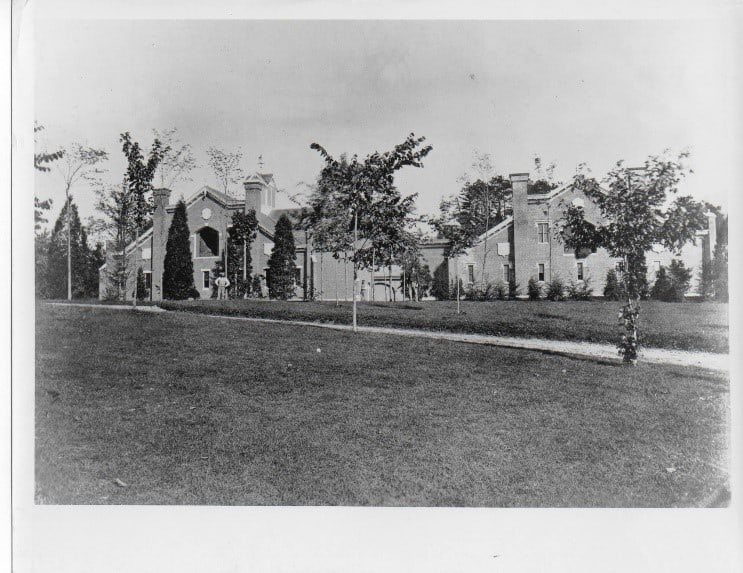

Known as ‘Knoll’ for its promontory location overlooking the Hudson, the Gothic Revival design of the house immediately drew attention. Critics called it “Paulding’s Folly” because of its fanciful turrets and asymmetrical outline which was unlike most homes constructed in the post-colonial era.

Paulding did not spend much time at Lyndhurst after its completion, opting instead for his family home in town. His son Philip R. Paulding, who had been chiefly involved with Davis designing and constructing “Knoll”, took up primary residence, until the 1850s.

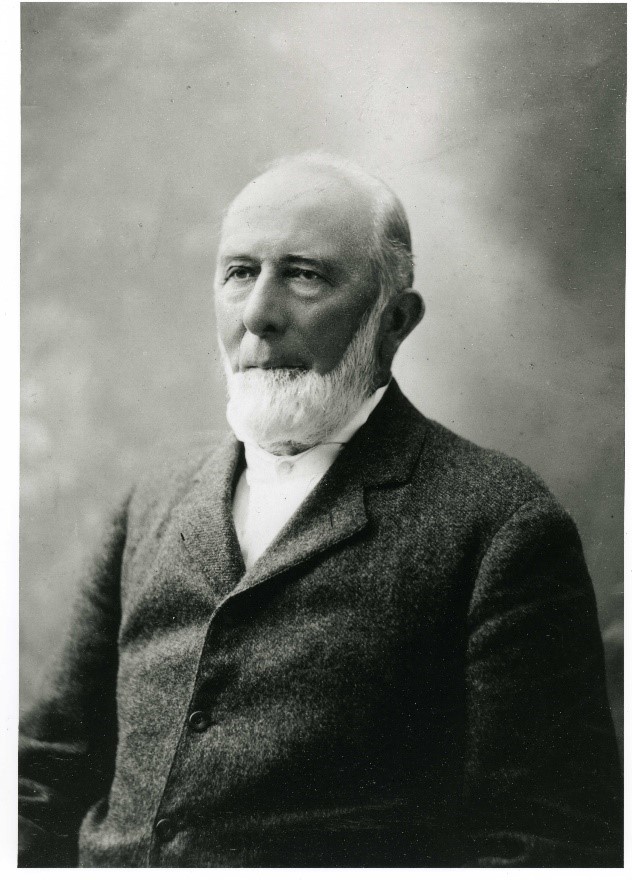

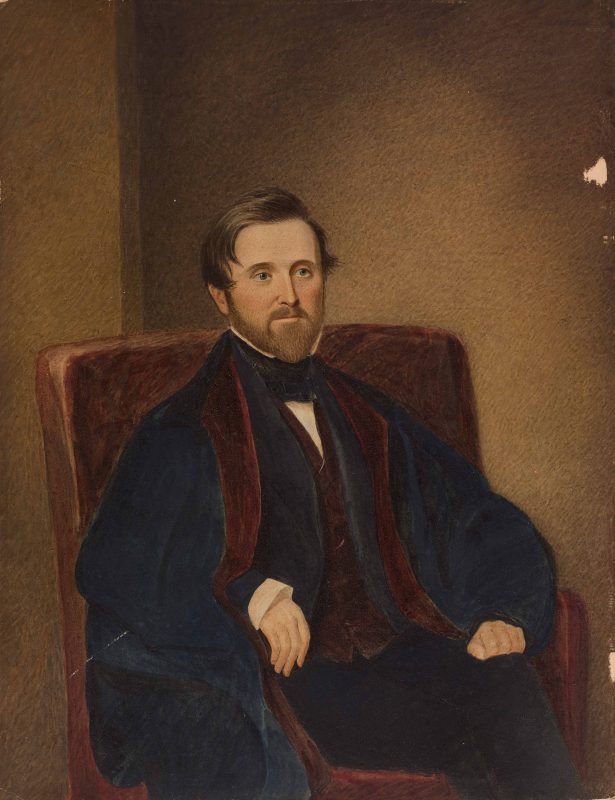

George Merritt, (1807-1873)

Fascination with the property continued for decades. As ideas of wealth and status changed with the growing nation, so did the estate, reflecting the tastes and interests of wealthy New York.

After the Pauldings had long since vacated ‘Knoll’, the property was sold to merchant George Merritt, in 1864. Looking to expand the house to accommodate his family and make it a full-time residence, Merritt brought architect Davis back to design the expansion of the house and update the gothic decorative finishes on the inside. During the expansion of 1864-65, a large addition to the north housed a new grander dining room, the second floor was expanded with additional bedrooms, and an impressive tower with the initials of Merritt’s children completed the changes making Lyndhurst one of America’s most impressive gothic revival homes.

|

|

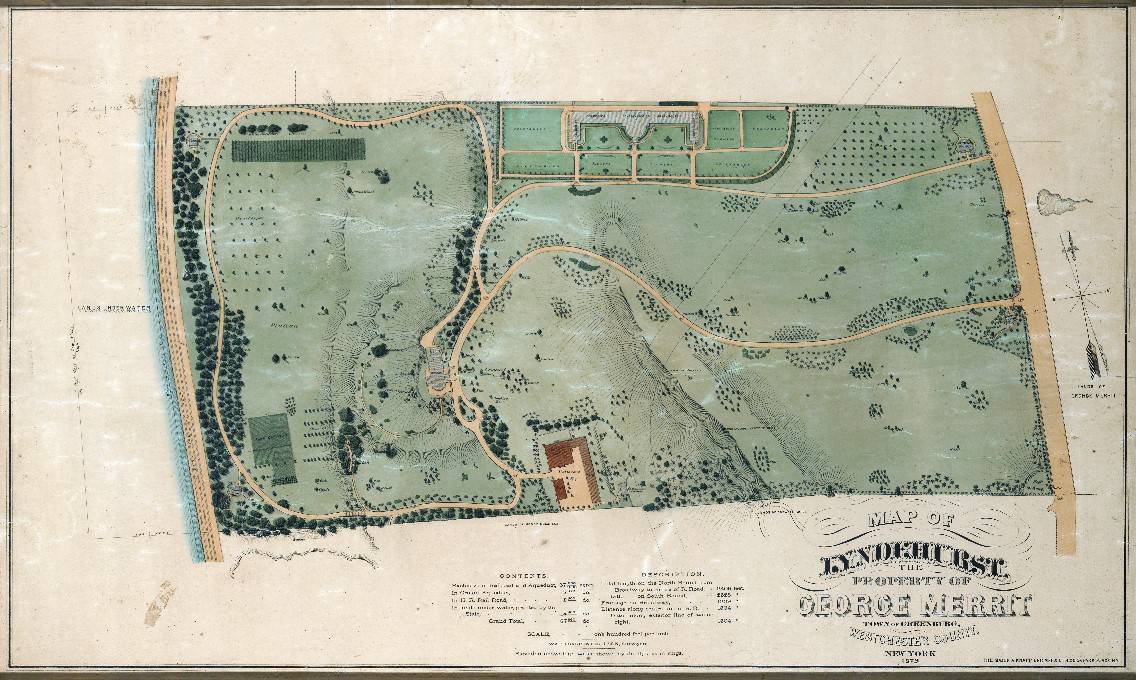

During his tenure, it is Merritt who began referring to his estate as ‘Lyndenhurst’ after the large Linden trees that he had planted on the grounds around the house.

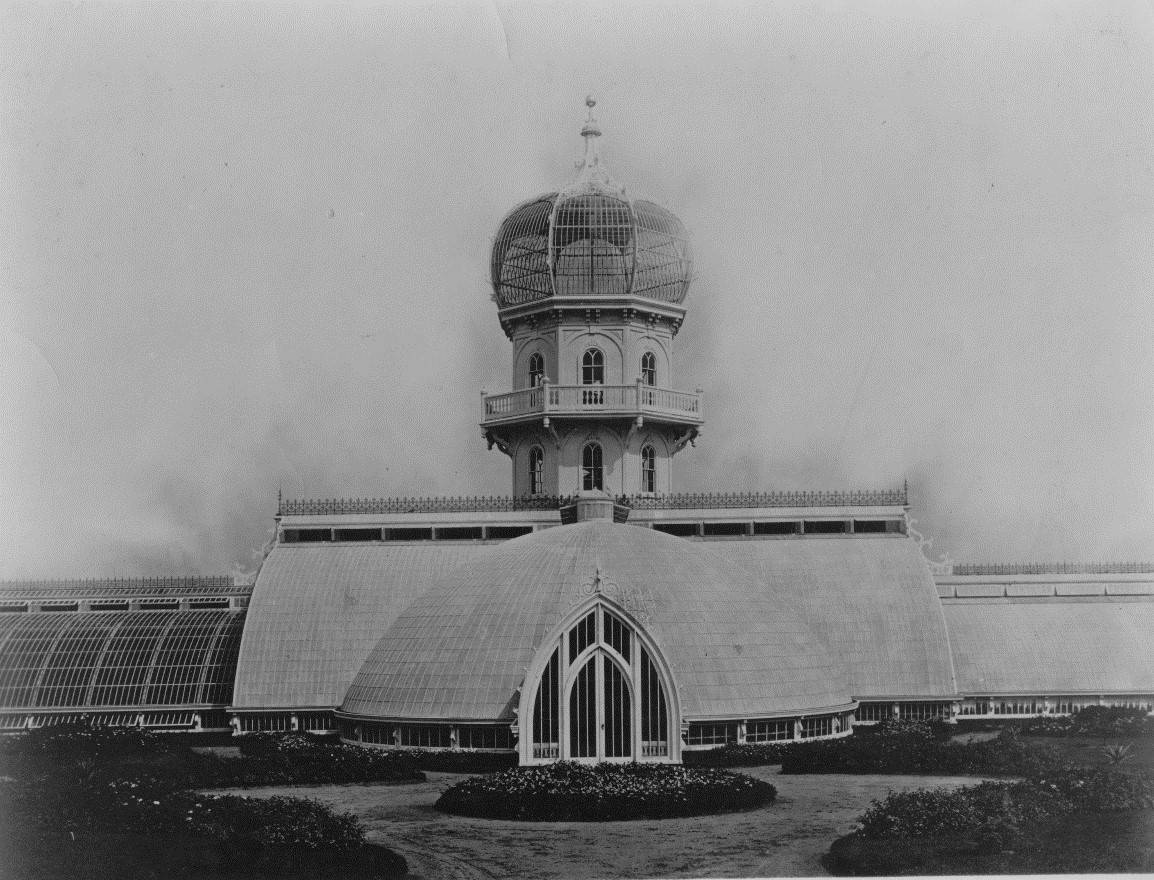

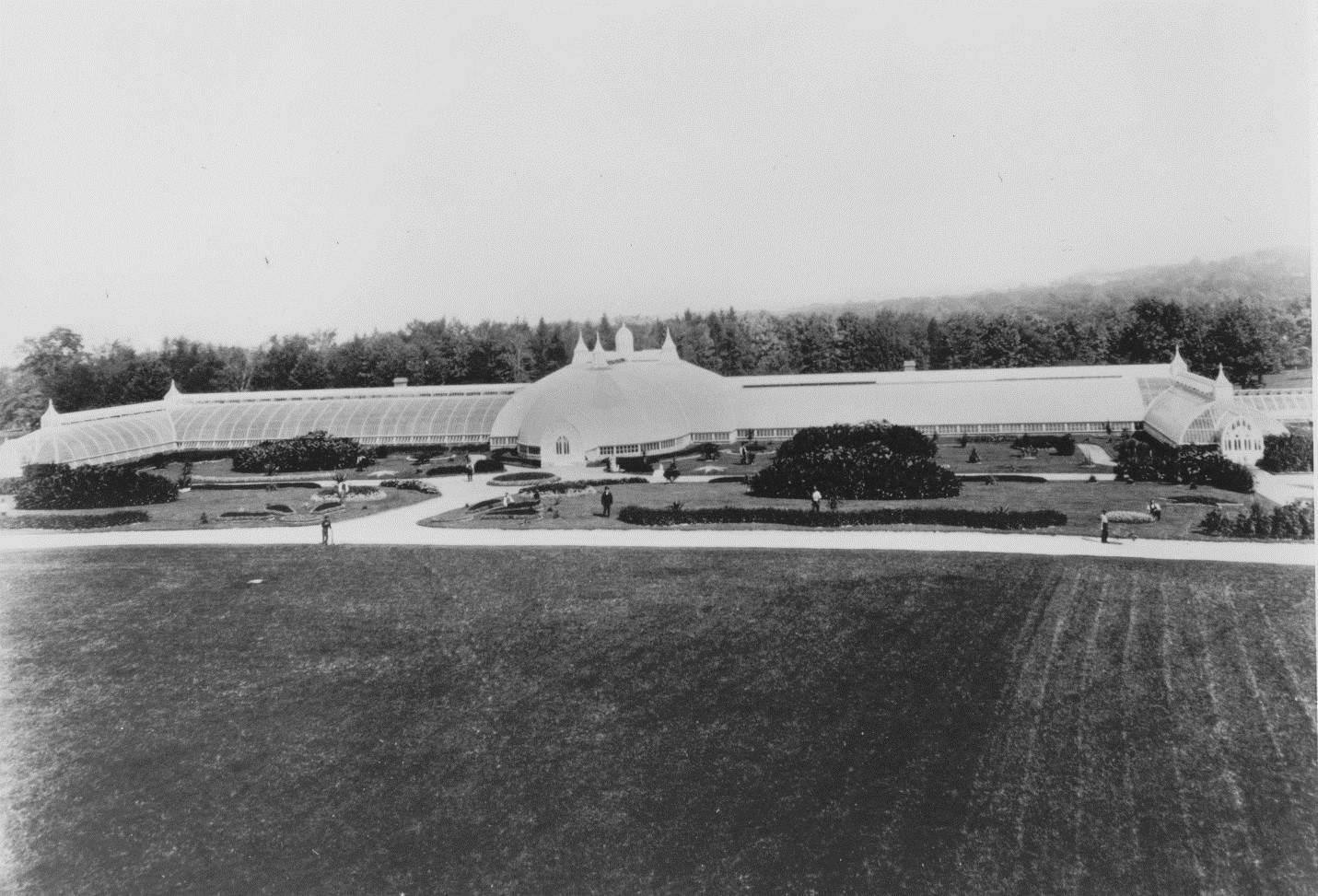

Merritt made changes to the mansion, but also made great changes to the landscape. While Paulding had kept the property as open farmland, Merritt’s Master Gardener, Ferdinand Mangold turned the grounds into a country estate. Bavarian-born, Mangold brought a European aesthetic to Lyndhurst, installing specimen trees, walkways to view the Hudson River, and a grand Moorish-style wood-framed greenhouse.

George Merritt did not live to enjoy Lyndhurst for very long and died in 1873, leaving behind his mostly grown children and his wife, Julia (1823-1904).

Faced with an expansive estate to run on her own, Julia made the decision to sell Lyndhurst.

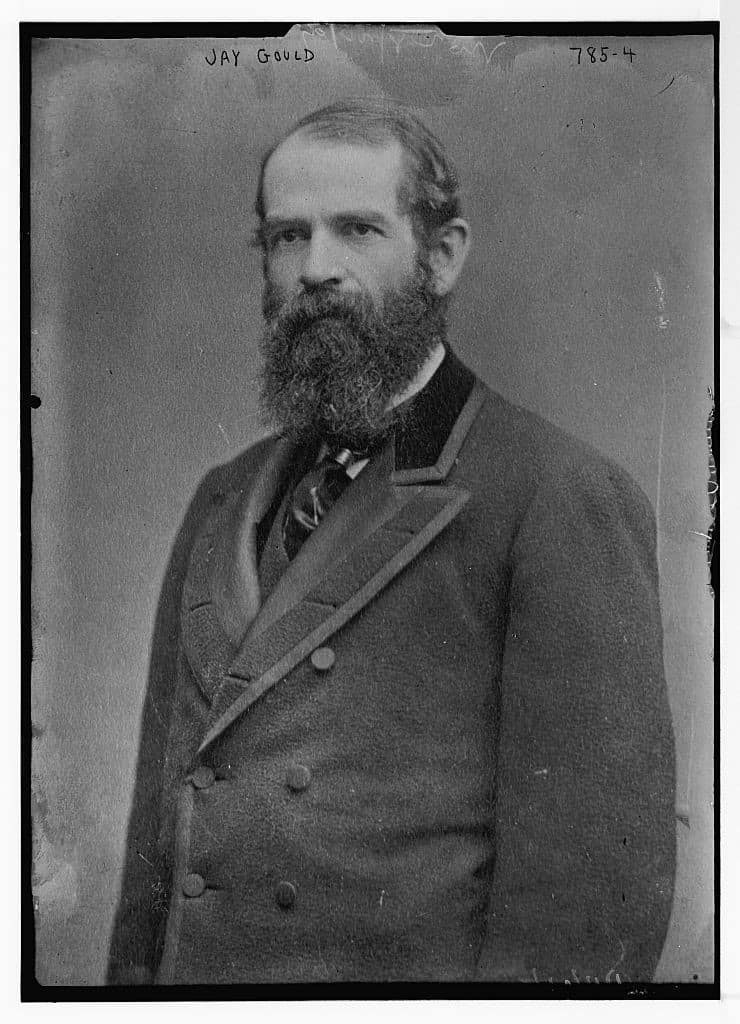

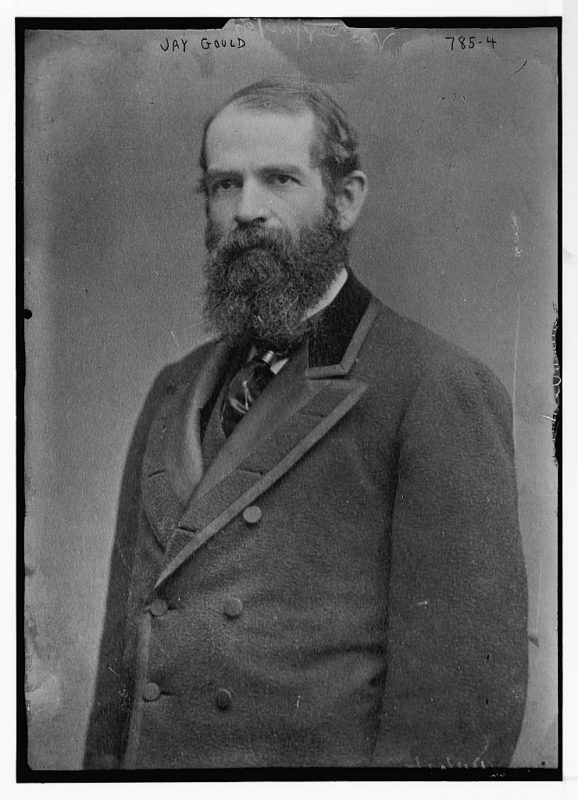

Jay Gould, (1836-1892)

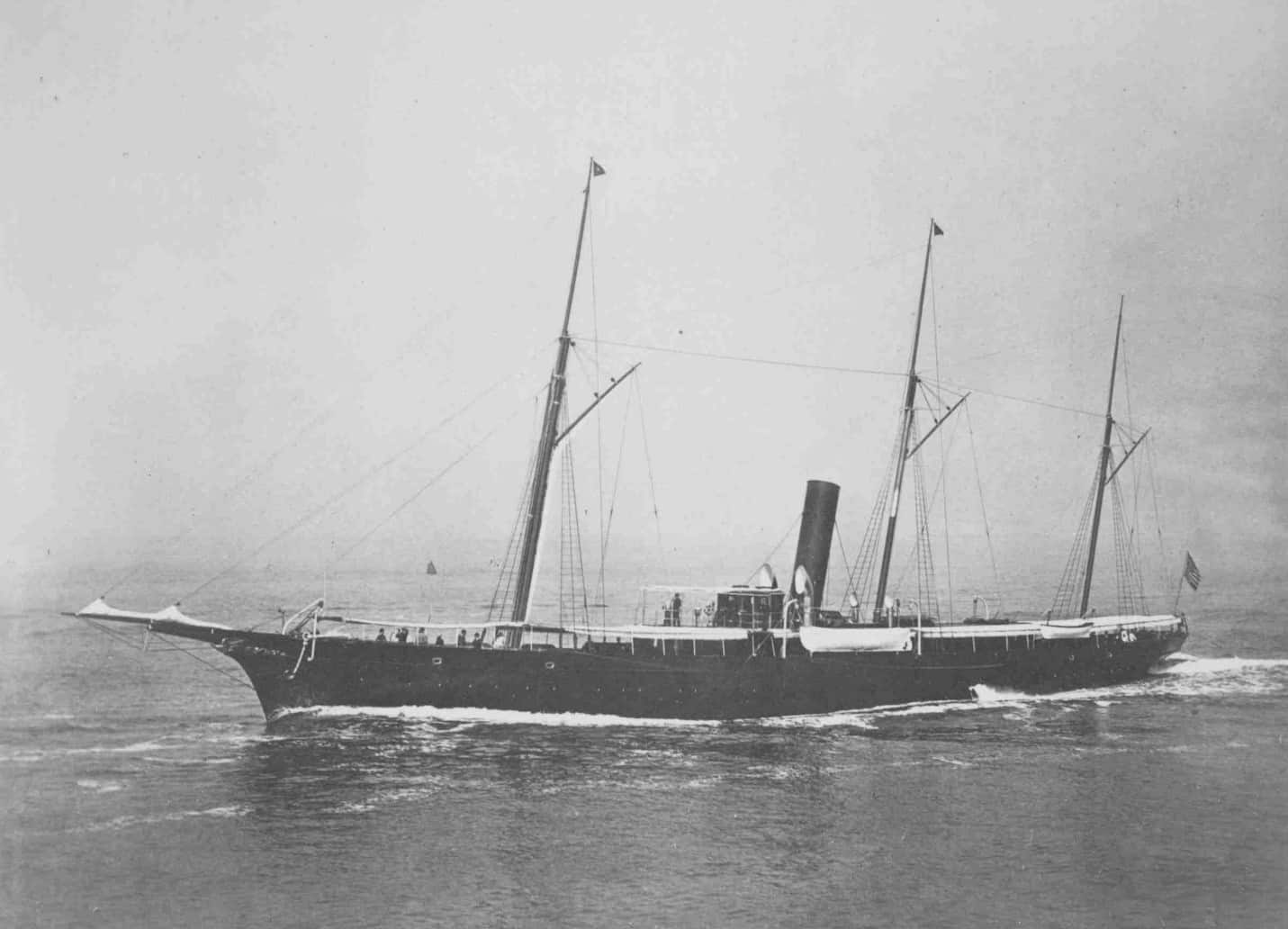

Railroad tycoon and financier Jay Gould purchased the estate in 1880, a few years after renting it as a family summer home and an escape from the pressures of business life in the city. Born and raised in the Catskill mountain town of Roxbury, NY Gould had a strong affection for nature and flowers and felt drawn to the estate by Merritt’s impressive greenhouse and its proximity to the city.

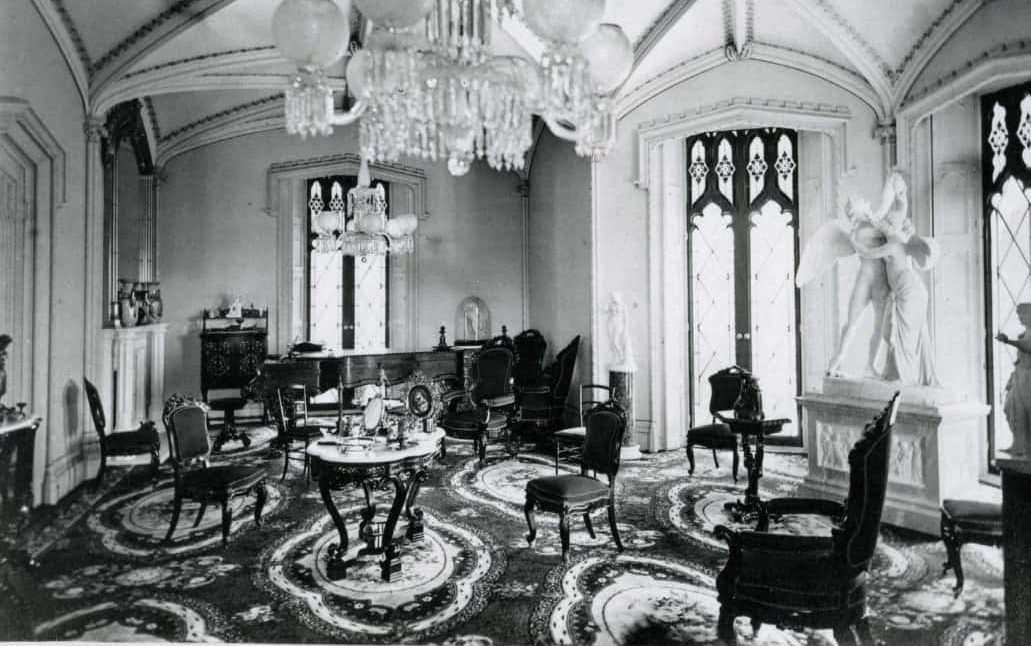

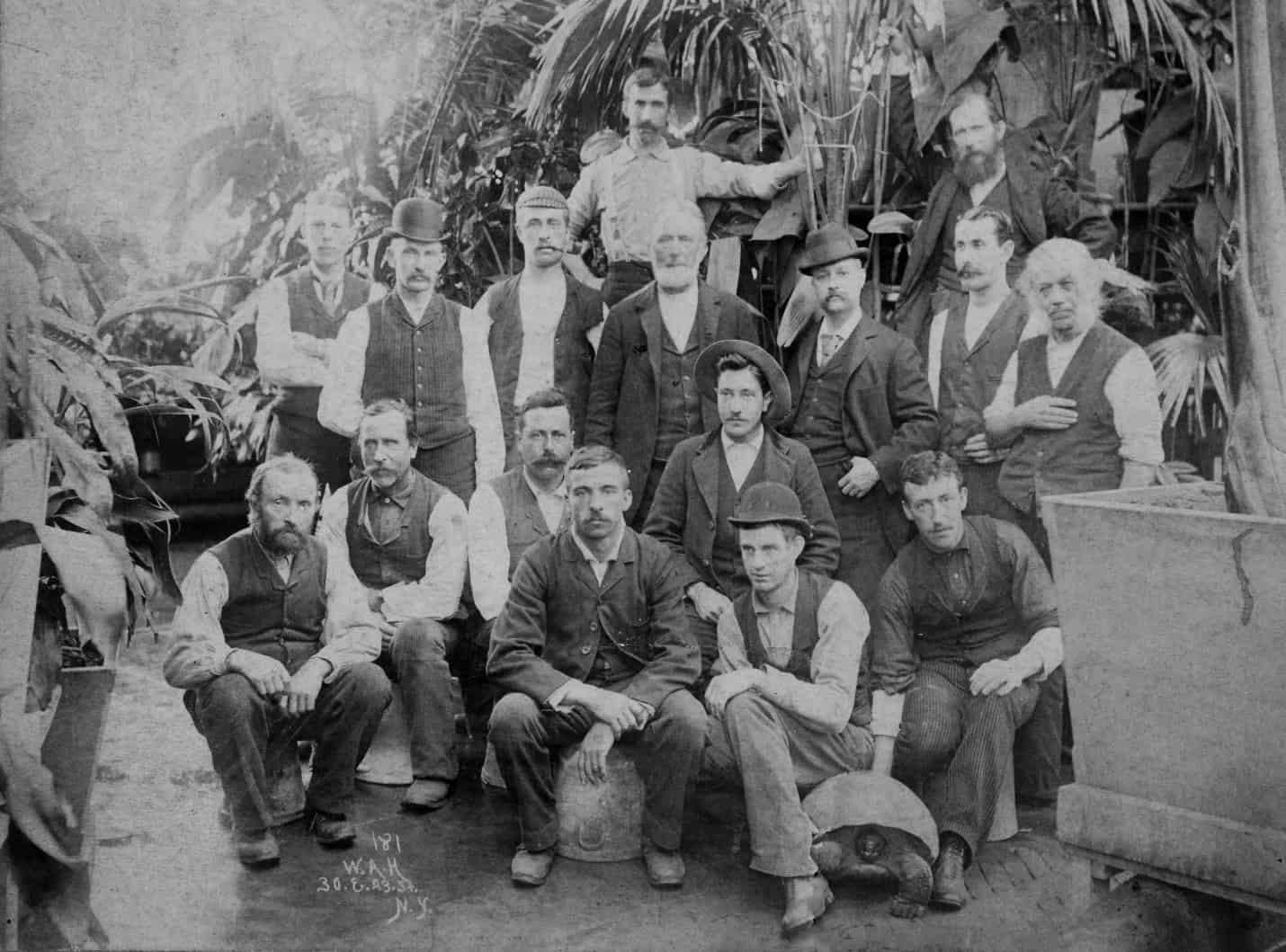

The Gould family spent many fond years at Lyndhurst, coming of age during the Gilded Age and splitting their time between Tarrytown and the city. Gould made little change to the house, opting instead to only update the décor and furniture. He also retained Master Gardner, Ferdinand Mangold, to continue to develop the grounds and run the greenhouse, now filled with Gould’s orchid collection.

Jay Gould’s wife, Helen ‘Nellie’ died in 1889, and in 1892, Jay himself finally succumbs to tuberculosis which plagued him most of his adult life.

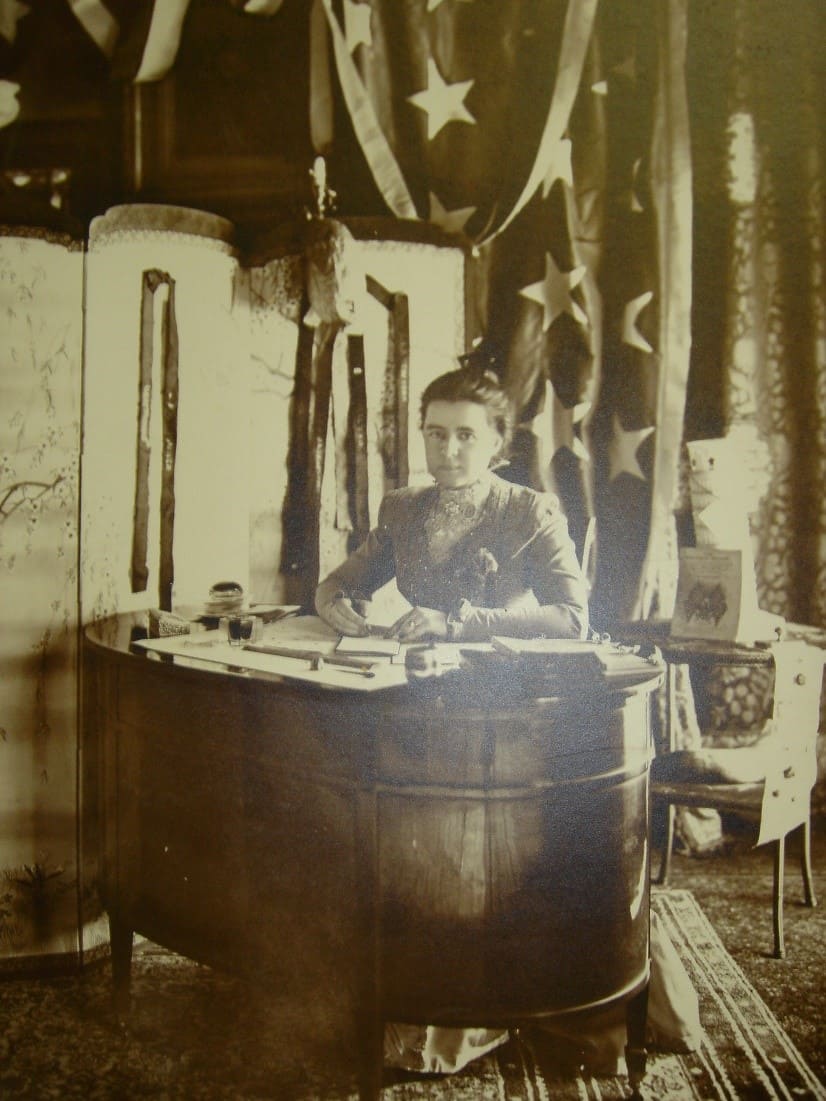

Helen Gould, (1868-1938)

Jay Gould’s eldest and devoted daughter, Helen, becomes the steward of Lyndhurst after her father’s death in 1892. Helen was a well-loved philanthropist and earned a law degree from NYS to manage her own finances. Having cherished the estate as a child, she continues to care for the estate as her father would have and utilizes it also for her own charitable endeavors. Helen added multiple buildings to the property including the Kennel, Laundry Building, Pool Building, and Bowling Alley.

During Helen’s stewardship, Lyndhurst’s estate became the site of free sewing, cooking, and carpentry schools for disadvantaged children so they could break the cycle of poverty. The massive greenhouse and pool building were open to the community six days a week. She actively supported women’s programs and educational schools for young ladies.

Helen married railroad executive Finley J. Shepard in 1913. They adopted three children and fostered a fourth. Much like when she was a child, Helen and Finley continued to use Lyndhurst as a seasonal home, spending time in New York City, her father’s hometown of Roxbury, and Lyndhurst.

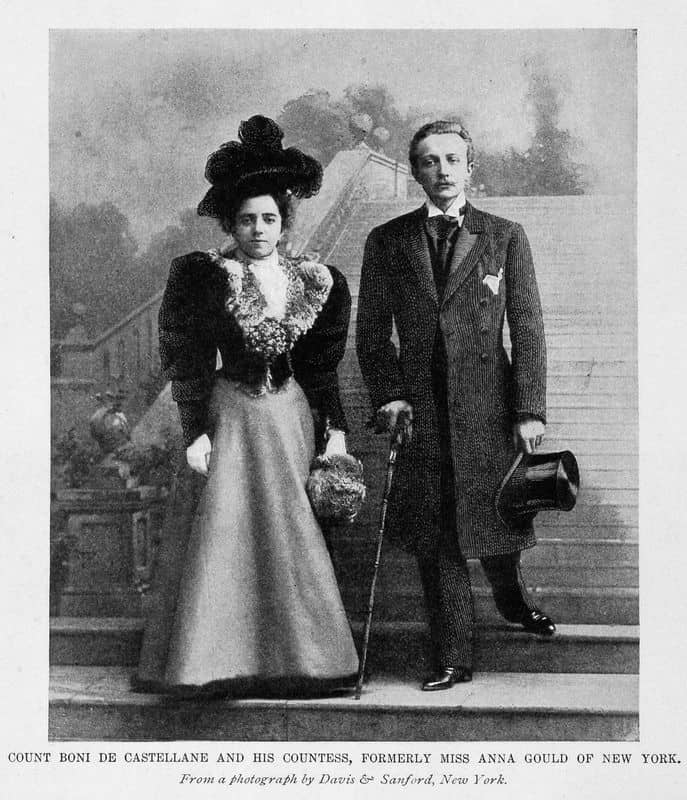

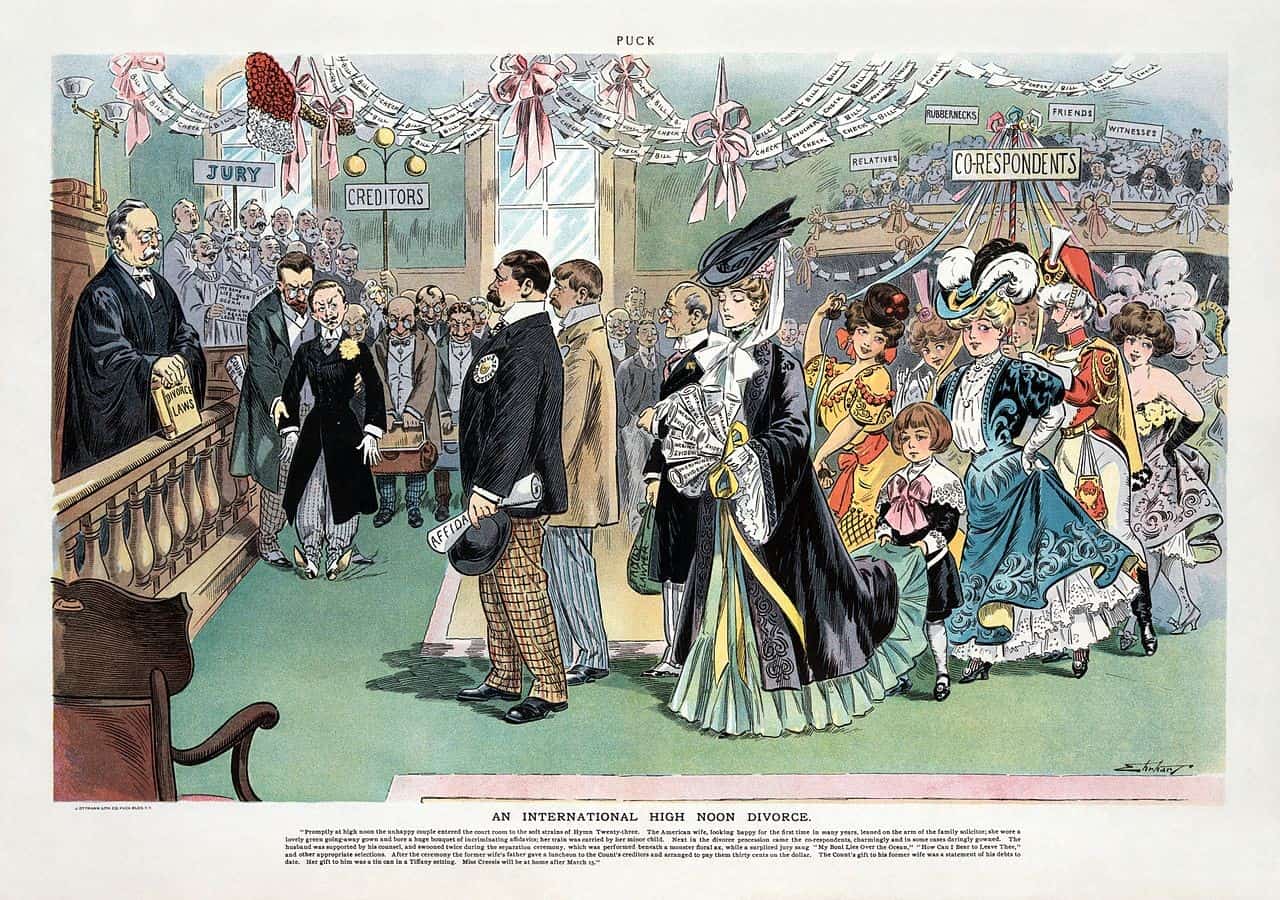

Anna Gould, Duchess of Talleyrand-Perigord (1875-1961)

The youngest Gould daughter, Anna, married young and into the French aristocracy. She lived most of her adult life in France and returned to the United States at the outset of World War II in Europe in 1936.

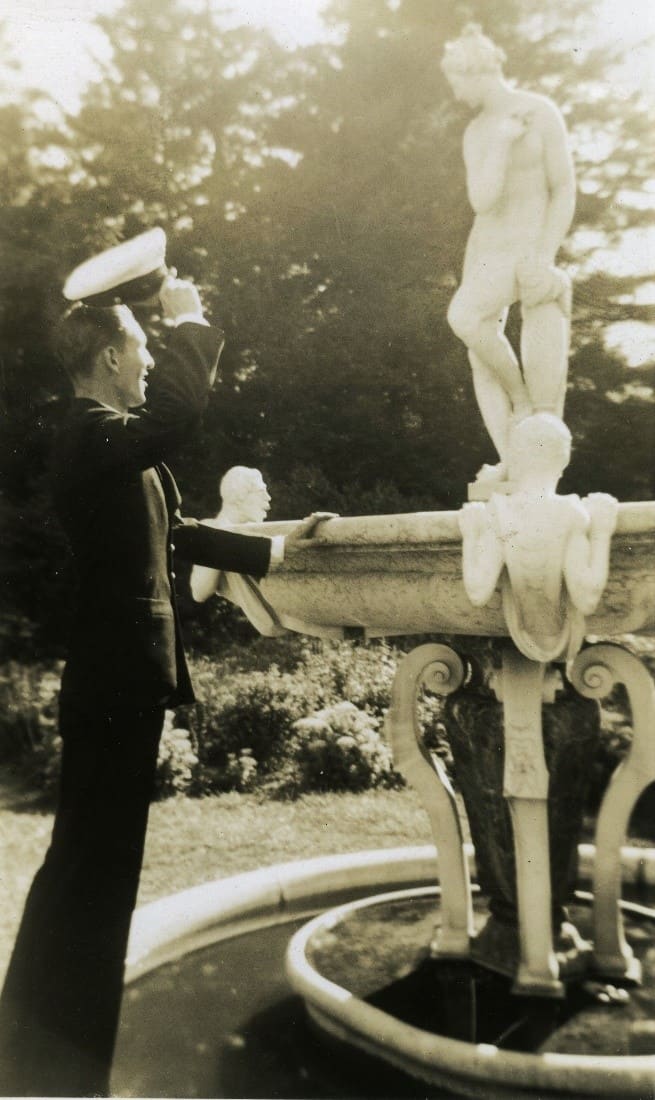

After her elder sister Helen’s death in 1938, Anna takes ownership of Lyndhurst and maintains Lyndhurst as a country home, primarily living at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. As a fashionable duchess, she was also known locally for opening the Lyndhurst estate to charitable efforts. Soldiers and seamen during the war convalesced on the property and off-site and she auctioned off the contents of the Lyndhurst Greenhouse to benefit the American Red Cross. Much like her sister, she made little changes to the inside of the house apart from bringing in personal decor and memorializing it and the grounds in the memory of her family who had lived there and enjoyed it for so many years.

She returned to France full-time after the war and passed away in 1961, bequeathing the entire estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It opened as a museum and historic site in 1965.

Designed in 1838 by Alexander Jackson Davis, Lyndhurst is considered to be one of America’s finest examples of Gothic architecture. The estate was shaped for more than a century by the three families that owned it and their influence is evident in the expansion of the house from a country villa “in the pointed style” to a Gothic mansion. Additionally, since Davis was in charge of the original construction and the later expansion, his interior decor and furnishing designs can still be found inside the house. The video below shows the evolution of the architectural changes at Lyndhurst mansion.