History of the Landscape

Lyndhurst has one of the most significant and well-documented Hudson River landscapes and its development spans from the 1840s to the 1960s and tracks the evolution of landscape fashions of the 19th and 20th centuries. Over successive generations, many existing features were preserved with selective additions made to bring the grounds up to date. The landscape never experienced a wholesale redesign and thus presents an excellent history of developing trends in the Hudson River over two centuries.

Lyndhurst’s landscape begins with the mansion’s architect Alexander Jackson Davis in the 1840s before his work with noted early landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing. Davis considered himself as much a picturesque landscape designer as an architect and the first iteration of the grounds at Lyndhurst were likely designed by him and captured in his watercolors and other drawings of the time. In 2017, Lyndhurst staff uncovered a series of Hudson River rock viewing areas that are possibly the work of Davis and could be one of the only surviving examples of his landscape work.

During the 1860s, Lyndhurst was further developed into a picturesque parkland landscape by Bavarian landscaper and Master Gardener, Ferdinand Mangold. Mangold brought the latest trends from European royal estates to Lyndhurst. He planted many of the trees and created features we see today. Mangold would stay employed at the estate until he died in 1905. The Lord & Burnham Company built the largest private greenhouse and likely the first fireproof greenhouse at Lyndhurst. After Mangold’s death, philanthropist and owner Helen Gould added garden elements in the early 20th century. Her younger sister, Anna Gould, Duchess of Talleyrand contributed garden sculptures and other marble features that still exist in Lyndhurst’s collections and are methodically being returned to the landscape.

The property is extremely well documented. Drawings and watercolors of the landscape exist from the 1840s and 50s. The property was photographed around 1870 and mapped to scale in 1873 (see above map). A full topographical utility map was commissioned by Helen Gould in 1905 after the death of Master Gardener Ferdinand Mangold and landscape photographs were taken in the 1920s by famed garden photographer Mattie Edwards Hewitt. There are aerial photographs from the 1960s and an in-depth landscape report was undertaken in the 1990s by Patricia O’Donnell and David Schuyler which utilized the memory of a landscape gardener who had been on the property since the 1960s and had worked for Anna Gould. A 30-minute 16mm film of the estate grounds was shot in 1942 by staff shortly after Helen Gould’s death and before Anna Gould took ownership. The film documents the lushness of the estate, including the details and color schemes of the floral bushes and perennial beds throughout the grounds that likely represent the earlier Gould period of ownership.

Lyndhurst is at the center of a group of land parcels that stretch from former large family estates (Pinkstone, the Lehman Family) down to Washington Irving’s Sunnyside comprising approximately 150 acres of woods and greenspace directly on the Hudson River. This is one of the largest parcels of Hudson River-adjacent land in lower Westchester and these parcels are connected by both the Old Croton Aqueduct and the Westchester Riverwalk.

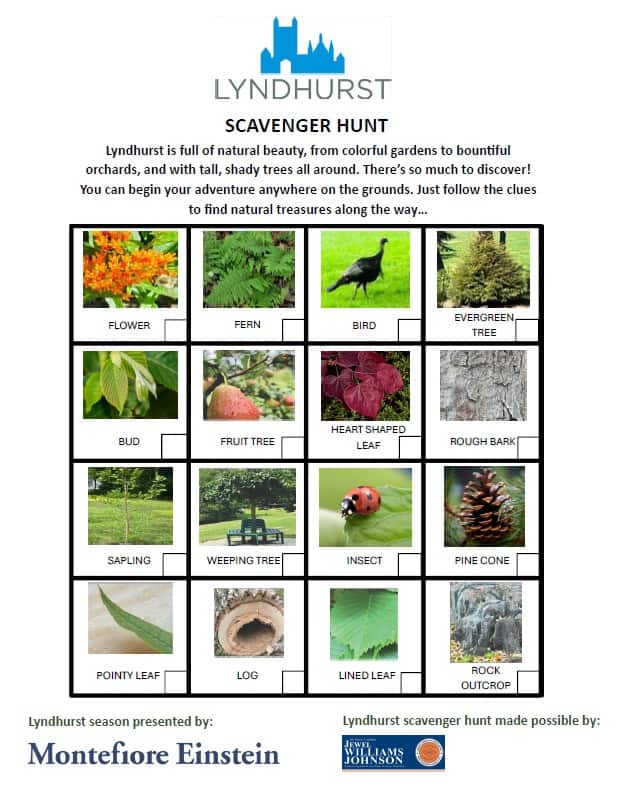

This family-friendly landscape scavenger hunt is available for pickup in our Welcome Center! See you if you can find all the things on the list! También disponible en español; ver más abajo.

Historic Rockeries

Rockeries are a 19th-century term used to describe outdoor seating areas used to seek shade and sun, and highlight the surrounding landscape perched on rocky outcroppings. When Davis returned to expand the mansion for the second owner, George Merritt, he possibly designed and added these features to the changing Lyndhurst landscape to create enjoyable outdoor spaces where people could promenade across the grounds, enjoy nature, and take in the picturesque views.

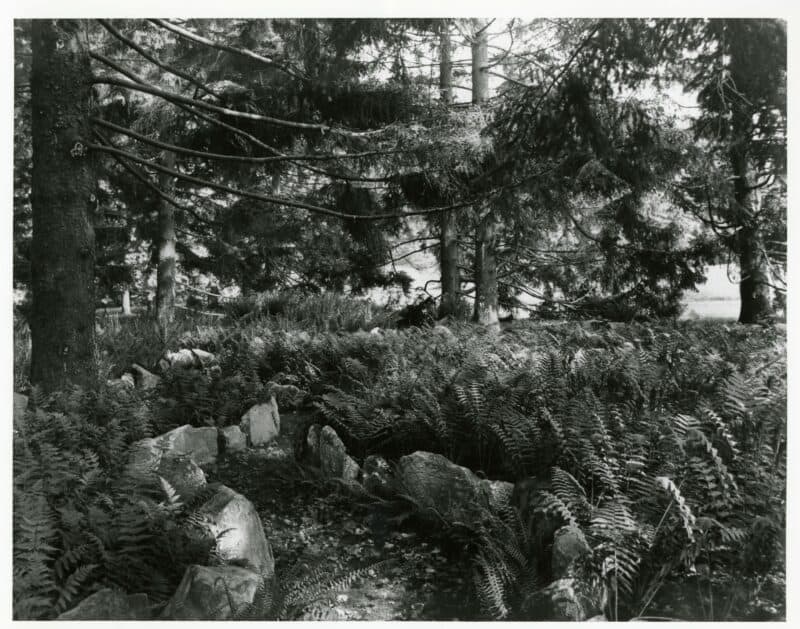

Survey maps from the 1870s show the three distinct sitting areas, situated on rocky outcroppings on the south and western slope around the mansion. Each appears to include a copse of shade-bearing trees, a specially designed bench for sitting, and walkways connecting them. Photographs from the same period reveal these rockeries, showcasing the lush undergrowth, specialty-created rock formations, and the photographer himself seated in the frame and timing the exposure.

Over the periods of ownership, these rockeries gradually faded away from the grounds. They were reclaimed mainly by the time the National Trust for Historic Preservation took ownership of the estate and turned it into a museum. The last remaining piece, the sidewalks, was then removed, and the lawn was allowed to grow in. In 2017, Lyndhurst staff discovered clues to the rockeries and their locations in the landscape. Work then commenced to restore the sidewalks and other hardscaping, followed by the benches and plantings, aiming to approximate the appearance of the historic photographs. As the trees and shrubs grow thicker each season, these sitting areas are slowly returning to their original shady hideaways where guests can rest and take in the beauty of the landscape around them.

Contemporary Rock Gardens

For over 20 years, the Hudson Valley Chapter of the North American Rock Garden Society has graciously planted and maintained the rock gardens at Lyndhurst. These gardens simulate mountainous terrain and the flowers that grow there. Most of the rocks were gathered from the property. They provide structure, moisture retention, and moderate weather conditions. The alpine plants that grow among them are mainly ground-hugging and tough survivors in a changing climate.

A special rock among the gardens is located on the walkway down from the mansion. This natural rock formation, with its curving, twisting metamorphic rock, reminds us there was a time when the material was in motion. Plants such as native bluets grow in the crevices and outline the curving rock.

In 2001, the Rock Garden Society added a new rock garden behind the Lyndhurst carriage house. In 2024, the garden was extended to include rare and native plants as well as a showcase for seasonal bulbs. Among Lyndhurst’s rock gardens, visitors will find an array of seasonal plantings, from dwarf Daphne and winter savory to Colorado cactus and petite bee balm. Volunteers are welcome!

Located near the entrance to Lyndhurst under a canopy of spruces and river birches, the Lyndhurst Fern Garden is home to one of the most comprehensive collections of hardy ferns in New York State. While the exact date of the garden’s creation is not known, it was likely established by Helen Gould Shepard in the early 20th century when she undertook other additions to the landscape, like the rose garden. The irregular beds, enclosed with stone palisades that separate the beds from the meandering paths, are characteristic of the romantic “picturesque” landscape style fashionable throughout the Victorian era, and the ferns represent the period of the later nineteenth century when “fern fever” spread to America from England. A photograph taken by American landscape photographer Mattie Edwards Hewitt in 1922 confirms the garden was well-established by that time.

By the 1980s, decades of neglect had left the garden overrun by brambles and poison ivy, and the rock borders had mostly collapsed. Only five native species of ferns survived. Thanks to the Taconic Men’s Garden Club and one of its members, John Corneal, who was also a Lyndhurst volunteer, restoration of the garden began in 1988. The late John Mickel, former Curator of Ferns at the New York Botanical Garden and an internationally recognized expert in the field selected the core collection of hardy species and varieties from around the northern hemisphere. Substantial grants from the Norcross Foundation enabled not only the acquisition of ferns but also the inclusion of deciduous river birch trees to replace the former failing evergreens.

In later years, the New York Fern Society took over the maintenance of the garden. Today, it is cared for by the Friends of the Lyndhurst Garden, a dedicated group of volunteers, in collaboration with Lyndhurst staff. The extensive garden contains over 100 different varieties from North America, Europe, and Asia. The beds are organized by genus and each variety is labeled with both its common and scientific names.

The Lyndhurst Fern Garden is an affiliate of the Hardy Fern Foundation:

The Rose Garden

The Rose Garden was developed during owner Helen Gould Shepard’s years at Lyndhurst in the early 20th century. Photographs taken around 1911-1913 reveal a mature garden with arched trellises, lush with pink climbing varieties. Upon Mrs. Shepard’s death, ownership of Lyndhurst passed to her younger sister Anna, the Duchess of Talleyrand-Périgord. During WW2, when garden help was largely unavailable, the rose garden was neglected and began to decline steadily. When the National Trust for Historic Preservation acquired Lyndhurst after Anna Gould died in 1961, only bare trellises and a few hardy roses were all that remained of the rose garden.

In 1968, at the request of the Lyndhurst Property Council of the National Trust, restoration of the garden commenced by the Garden Club of Irvington. In the fall of that year, members of the Garden Club of Irvington began the project by painting the trellises, and in the following spring, they planted the climbing roses and a portion of the planned circle beds. Three years later, the garden with its 24 crescent-shaped beds, in three tiers, was finished. Two small westernmost beds were added in 1974.

For many years, the Garden Club of Irvington has cared for the garden, dedicating thousands of hours and raising thousands of dollars for its maintenance and renewal, which has elevated it to award-winning status. Noted American Rose Society Consulting Rosarian, Dr. Cynthia Westcott, author of Anyone Can Grow Roses, provided advice on the design and plant selection during that time.

The garden suffered greatly from damage by the ever-increasing deer population. By the autumn of 1999, only the tallest shrubs and the tops of arbors retained some leaves and blooms due to the voracious appetite of the deer. Responding to the crisis, the Property Council of Lyndhurst permitted the installation of a 10 foot fence along the outer perimeter of the garden area. With this protection in place, the rose garden flourished once more. Today, it continues to thrive, with care and maintenance shared by Lyndhurst Staff and Rosarian Ann Perkowski and her crew of Lady Clippers.

The present plantings do not replicate Mrs. Shepard’s original design.  While we seek to echo the early garden’s lush beauty and tranquility, a broader spectrum of colors and varieties is now found amongst the beds. The garden, which once contained some 500 roses in Helen’s time, currently contains approximately 250 roses, including the climbing roses that decorate the arched trellises. Most of the shrub and old garden roses are planted in the outer circle of beds, while hybrid teas and grandiflora roses fill the middle circle, mixed with a few old garden or shrub roses. Polyanthas and floribundas are planted in the innermost circle. Lyndhurst Staff have recently begun to re-label the roses by type and date of introduction, as the legacy continues.

While we seek to echo the early garden’s lush beauty and tranquility, a broader spectrum of colors and varieties is now found amongst the beds. The garden, which once contained some 500 roses in Helen’s time, currently contains approximately 250 roses, including the climbing roses that decorate the arched trellises. Most of the shrub and old garden roses are planted in the outer circle of beds, while hybrid teas and grandiflora roses fill the middle circle, mixed with a few old garden or shrub roses. Polyanthas and floribundas are planted in the innermost circle. Lyndhurst Staff have recently begun to re-label the roses by type and date of introduction, as the legacy continues.

The Greenhouse Environs